Brazilian rappers are giving voice to the anger many feel towards a new political establishment led by a president seen as racist, sexist and authoritar

RIO DE JANEIRO — When rapper Gustavo Ribeiro was working on his new album, he lost count of the number of times he had to stop writing or recording because the protests outside his apartment in São Paulo were too loud.

It was the end of 2018 and Brazil was going through its most-fraught presidential elections in decades. Brazilians were polarized over what many viewed as a thankless choice: voting for a candidate from the Workers’ Party, which had lifted millions out of poverty but also overseen the most massive corruption scandal in the country’s history, or electing Jair Bolsonaro, an extreme-right wing politician.

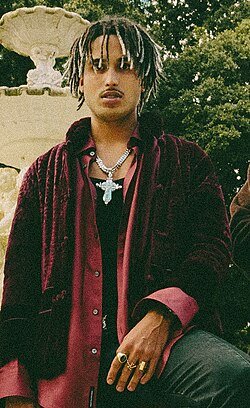

After the results came in, Ribeiro, who goes by Black Alien, was angry Brazilians had chosen Bolsonaro for president, ignoring the bigotry many accuse him of. So he included a song about it, “Jamais Serão” (“There Never Will Be”) in his new album, Hello Hell.

What I really think is that presidents are temporary, baby,” the song’s chorus goes. “Good music is forever and these losers never will be.”

At first, Ribeiro didn’t set out to write about politics, as he frequently did when he started his career in the 1980s. But lately, as rap steps up the ladder into the mainstream of Brazilian music, fight-the-power songs have been sharing more space on radio and streaming airwaves with music about love and sex.

As rappers experience a new wave of popularity in Brazil, they have also become uniquely positioned to give voice to the anger many feel towards a new political establishment led by a president seen as racist, sexist and authoritarian.

“I can’t waste the valuable instrument that is rap [and not] talk to people, to young people mainly, here in Brazil, an obnoxiously stupid country that doesn’t educate people,” Ribeiro tells Billboard. “Half of the people voted for this deadbeat out of ignorance.”

Lyrics aimed at criticizing Bolsonaro and his political platform — or resisting it — are popping up in rap more than in any other type of music.

Meanwhile, right-wing rappers have been writing about the rise of Bolsonaro in a tone of praise, with songs such as “Meu filho vai ser bolsonarista” (“My son will be a bolsonarist“) and “Carta ao Bolsonaro” (“Letter to Bolsonaro“).

“I live in a favela, I’m of African descent and a police officer,” sings PapaMike on “Letter to Bolsonaro,” whose video calls out corrupt business executives and depicts the new president aiming an automatic rifle. “I’m in the middle of chaos, a survivor of the war. And your name is growing in the fight against evil.”

ADVERTISEMENT

But pro-Bolsonaro rap is still niche, and doesn’t receive nearly as many views as anti-Bolsonaro tracks.

Artists with stronger fan bases such as Djonga — who has more than 1 million followers on YouTube, the most efficient thermometer for Brazilian music — are using their music to share their thoughts about politics.

“And it looks like prejudice was set loose,” Djonga writes in “Hat-Trick”, which has over 2.9 million views. “At least in the old days these assholes were discrete.”

The rap protest movement is rooted partly in the broader spread of local language hip hop, a streaming-fueled phenomenon taking hold across many countries, including in Brazil, the 10th-largest music market in the world. Brazil’s subscription audio streams grew by 53% in 2018, to $151.6 million, according to the IFPI.

But in Brazil, politics is also playing a role.

“In this polarized moment, with the extreme-right making a comeback, people are in need of being represented, so they can affirm their ideology,” says Leo Morel, a Latin American music analyst at Midia Research. “People might be looking to rap for a voice that represents them.”

Related

Rappers have become some of the loudest voices against the Bolsonaro administration, and sharp critics of the left’s failure to defeat him and to connect with people in Brazil’s slums and ghettos.

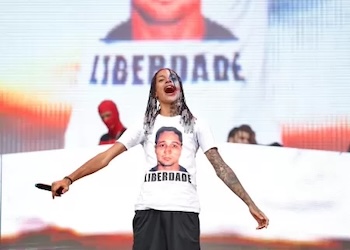

That much became obvious when rapper Mano Brown took the stage at a leftist rally last October to criticize Brazil’s Workers Party, days before the party lost the elections to Bolsonaro.

“Those who made mistakes are going to have to pay,” Brown said, in what might have been a nudge to the dozens of corruption charges against party members for allegedly participating in a more than $2 billion bribery scandal. “If you don’t understand people anymore, you’re done.”

Brown is a member of Racionais MC’s, Brazil’s most traditional hip-hop group. This year, the group went on a country-wide tour to celebrate its 30th anniversary.

ADVERTISEMENT

Other older rappers are also making comebacks. Planet Hemp, a rap-rock group known for starting the careers of rappers Marcelo D2 and BNegão, is releasing its first album since 2001 early next year. It will be full of protest songs, he promises Billboard.

He already has started: “The patriot gently gives his people’s lands and souls to North America,” goes one song, “Blá Blá Blá,” (“Blah Blah Blah”), which he wrote for singer Elza Soares’s new album, Planeta Fome (Hunger Planet).

Songs confronting the status quo are not the only type of politics rappers have been delivering. They also have tried to motivate fans into resisting soul-crushing times.

“People don’t just want that crude, naked report on reality,” explains MV Bill, a rapper based in Rio de Janeiro. “There is also this motivation thing, being proud of who I am.”

In a recent song, called “Rapsistência,” or “Rapsistance,” he urges listeners not to accept a hate-filled agenda: “To fight the unlikely, we build several bridges; those who owe us, who are all talk, we destroy on our way.”

Perhaps the most popular example of a song of resistance and motivation is Emicida’s “AmarElo” (“Yellow”). The last section of the song goes: “Raise you head high; wipe away those tears, ok? (Yes, you); take a deep breath and go back to the ring (go); you will get out of this prison; you will go after this diploma.”

When he released the track in June, it seemed like the whole of Brazil stopped to listen and let the lyrics sink in. Many posted parts of “AmarElo” to social media and the song drew 1 million views on YouTube in its first two days, according to tracking done by Emicida’s Facebook page.

Racism and black pride are perhaps the most frequent themes in the new wave of political rap songs. Baco Exu do Blues’ single Bluesman won a Grand Prix award at the Cannes Film Festival last year for a music video depicting the life of a young black man. The short film challenges preconceptions of race and self-worth.

“They want black people with guns in the air; in a music video in a favela yelling: Cocaine; they want our skin to be the skin of crime,” it goes. “They are fucking scared of the next Obama….”

Though rap is clearly making a comeback in Brazil, some older rappers say they feel frustrated. After Bolsonaro was elected, Ribeiro wondered whether anyone had been listening to his work over the past two decades.

Brown, from Racionais MC’s, has already made it clear in concerts that he won’t write more protest songs in a country that votes for Bolsonaro. “I prefer to be alone with my own demons,” he said on Twitter.

But others, such as Ribeiro, see the current political landscape as a push to keep going. “Looking ahead, I’ll start to talk more about politics,” Ribeiro says. “I think we need it. We need it a lot.”

Get weekly rundowns straight to your inbox